LANDSCAPES. A SIGHTSEEING LESSON

Keywords: sightseeing, heritage tourism, micro-expeditions, locality, stay-cation, outdoor heritage education, landscape photography, photo archives

The lesson we propose is designed to help answer the following questions:

– What is contemporary heritage tourism?

– How to teach about your region through action, encouraging students to acquire knowledge creatively on their own?

– How can a photographic archive help you get to know your surroundings better and look at well-known places from a different angle, and what can you discover in the process?

– How can creative field trips and photo archives enrich teachers’ work tools?

The lesson’s scenario is devised as a collection of inspirations and hints for teachers on how to enrich their educational activities with aids offered by ‘new heritage tourism.’ It is based on our specific experiences and clues, which we encourage teachers, educators, and culture animators to pick up on. In particular, the examples we present here may prove interesting for schools, which are constantly short of breath in trying to fully deliver the core curriculum. Outdoor heritage exploration is useful as a means of taking at least some educational activities out of the school walls, if not during educational classes themselves, then during homerooms or extracurricular and interest group classes.

Part 1 – NEW HERITAGE TOURISM

A. HERITAGE TOURISM

In order to explain what ‘new heritage tourism’ is, it is worth looking at what heritage tourism was like in Poland in the late 19th/early 20th centuries, when it emerged. At the time, it had a political dimension and was meant to awaken patriotic feelings in Poles towards their country, which was being reborn after the partitions. By the time, leisure tourism had already developed strongly in Europe. The development of railways, the emergence of the automotive industry, the use of steam engine in shipping – the technological revolution, made moving between cities or countries much easier and cheaper. The period also saw the establishment of the earliest travel agencies. The origins of leisure travel can be traced back to one Sunday in 1841, when Thomas Cook, who later founded a world-famous travel agency, organised a rail trip from Leicester to Loughborough. It was a trip for 570 people who wanted to attend a teetotaller rally, in which Cook himself took part. He believed that it was a better idea for factory workers to go on a trip than spend money on alcohol. Later, he organised trips to Liverpool, Glasgow and Edinburgh, and after 1864, also to foreign countries, including France, Switzerland, and Italy.

In Poland, which did not exist at the time, mass tourism was not yet able to develop on such a scale. Travel, especially abroad, was only available to a very narrow financial elite. The relatively few and rather poor bourgeoisie could not afford to indulge in recreational tourism on a mass scale, which was why heritage tourism gained such importance in the interwar period.

Heritage tourism was a political project. The organisation of trips, publication of guides or maps, and popularisation of knowledge about Poland was primarily aimed at strengthening the Polish national identity. Such ideas were professed, among others, by Aleksander Janowski, who was a father of the Polish heritage tourism movement. When he went on his first trip, from Sosnowiec to Zawiercie, and then hiked to the castle in Ogrodzieniec, and after a forced overnight stay caused by a storm, he returned with an outline of his own idea of heritage tourism. He summarised his reflections on heritage tourism as follows:

– The love of your homeland makes you desire to make it happy by serving it with dedication irrespective of your social position and in every walk of life.

– Getting closer to your native nature awakens a sense of the powerfulness of your homeland, and getting closer to the people stirs up brotherly love and a sense of community, multiplying your strength as an individual. Meanwhile, work to popularise heritage tourism gives you courage and faith in the power of the state, arouses noble pride and national dignity, shaping your character and elevating you to a higher category of citizen.

– Work to promote heritage tourism is a state-forming factor and as such should gain fervent followers in society, who should become the co-creators of collective happiness and builders of the power of the homeland.

Testament krajoznawczy Aleksandra Janowskiego (w stulecie urodzin), [in:] Władysław Szafer, Z teki przyrodnika, ed. I, vol. II, Warsaw: PW „Wiedza Powszechna”, 1967.

Similar ideas were propagated by other Polish promoters of heritage tourism of the early 20th century, including Zygmunt Gloger, Kazimierz Kulwieć, and Ludomir Sawicki, who founded the Polish Heritage Tourism Society in 1906, based on the above assumptions. Ludomir Sawicki founded the Polish Geographical Society in 1918.

B. HERITAGE TOURISM 2.0 AS SEEN BY TOWARZYSTWO KRAJOZNAWCZE ‘KRAJOBRAZ’

We built what can be referred to as ‘second-generation heritage tourism’ on completely different foundations than it was the case with early 20th-century heritage tourism. Our fascination with locality, with what is close and understandable, evolved not so much from the need to instil patriotic attitudes, but from our simple desire to spend time outdoors.

Our successive travels to ever more exotic destinations made us growingly disappointed with the authenticity of that experience. We started to perceive tourist attractions offered by travel agencies or described in guidebooks as rather boring – there was nothing to discover, because everything was served on a plate. Meanwhile, we were into adventures, discovery and exploration of the unknown. We consciously gave up exoticism and replaced it with local attractions and curiosities. We started to value lonely wandering in the Augustów Forest more than queuing to see the Iguazu Falls. That sense of declining authenticity of our tourist experience prompted us to turn to heritage tourism.

The three pillars of the ‘new heritage tourism’ are as follows:

1. Active time spending outdoors.

2. Being fed up with commercial tourism. Tourism has become a huge industry that offers the same ‘holiday products’ for millions of consumers.

3. Concern for the environment. Flygskam or flight shame is a movement initiated in Sweden. We do not segregate rubbish, drive electric cars, promote green energy to finally get on a plane and fly to Paris for the weekend, thereby emitting so much carbon dioxide into the atmosphere that our ‘green’ activities at home lose any sense. This made us stop traveling far and switch to public transport, a canoe, bicycle or cross-country skiing.

C. EXAMPLES

In order to illustrate how we in the ‘Krajobraz’ Society understand and practice new heritage tourism, here is an overview of our projects from recent years:

- Polska Nie_odległa

The project was prepared for the 100th anniversary of Poland’s independence.

‘Polska Nie_odległa’ is a play on words. In Polish, Nieodległa means ‘not far away’ and sounds like Niepodległa, which means ‘independent’. Thanks to those who sought to regain independence a hundred years ago, we can freely travel around Poland today, discovering the country’s local culture and nature. It is a great way for us to celebrate attachment to a Poland that is diverse, non-obvious and full of interesting facts and charming spots.

The earliest Polish promoters of heritage tourism would emphasise that getting to know your country was the first step towards mature patriotism and developing a civic attitude. With the project, we encouraged anyone to find out for themselves.

We invited people to venture into a hundred local ‘heritage exploration feats’, i.e. travel to interesting, non-obvious places.

We proposed 50 ‘heritage exploration feats’ that were available to everyone, for example: reach the highest peak of your poviat, get on a random train, brush your teeth in Niemyje-Ząbki (town name, which translates as “I don’t wash my teeth” into English), visit one of the places depicted in the Polish banknotes, etc. Another 50 feats were to be proposed by the participants themselves (today the official list consists of 127 feats). While performing the feat, you were supposed to take a picture of yourself on the spot and then upload it to a social network with a hashtag or send it to us.

photo: ‘Polska Nie_odległa’

- The Giants of Heritage Tourism

On the wave of popularity of historical re-enactment in Poland, we organised re-enactments of heritage exploration trips.

By redirecting attention from battlefields to tourist routes and from the names of great leaders to names known to a small group of enthusiasts, we tried to show the relationship between the travel routes of the earliest heritage explorers and the present-day identity of the individual regions and the way we talk about places, their history and culture, today.

The Giants of Heritage Tourism combine the experience of trips treated with a grain of salt, based on the explorative convention that is embraced so perfectly by the participants of our campaigns, with educational activities where we focus on events, figures and places important to Polish history and identity.

https://krajobraz.org/giganci-krajoznawstwa-rekonstrukcje/

photo: Tomasz Kaczor, Zawiercie

Part 2 - LANDSCAPE PHOTOGRAPHY AS A FORM OF HERITAGE TOURISM – on the example of Paweł Pierściński’s archive

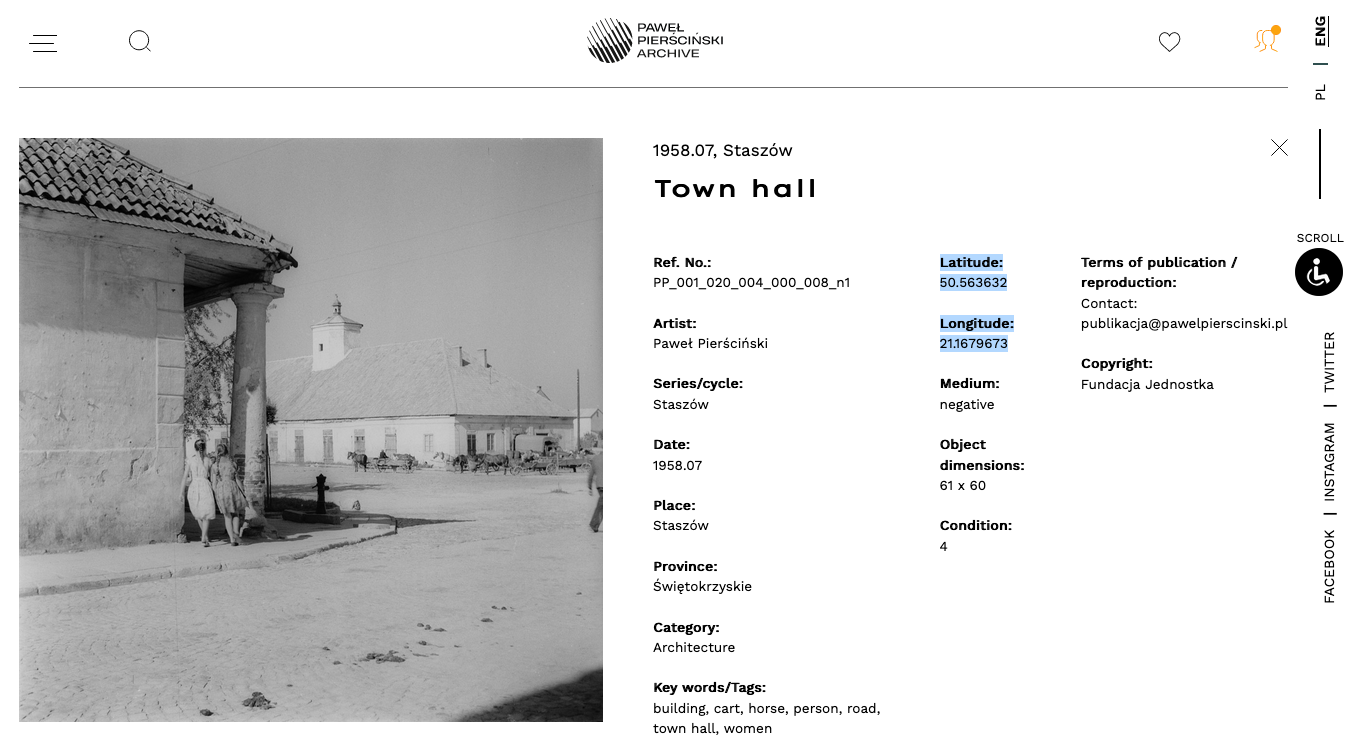

Paweł Pierściński was a photographer and a heritage explorer. A civil engineer by education, he was supposed to build the Warsaw metro, but because the project was abandoned after the initial test drills, he gave up his profession and devoted himself entirely to photography. In practicing the latter, he pursued his passion for mathematics, which is evidenced by his depictions of the Kielce landscapes, many of which are abstract geometric compositions. He described himself as a documenter exploring photographically the world of structures existing in scenery. The landscapes of the Kielce and Ponidzie regions were his artistic homeland and the main artistic inspiration. He travelled with his camera around Poland from the 1950s almost until the end of his life in 2017.

Pierściński’s photographic interpretations of Kielce landscapes have now become the classics of Polish art photography. He and his colleagues from the Kielce branch of the Polish Photographic Society founded a movement which has gone down in history as the Kielce School of Landscape.

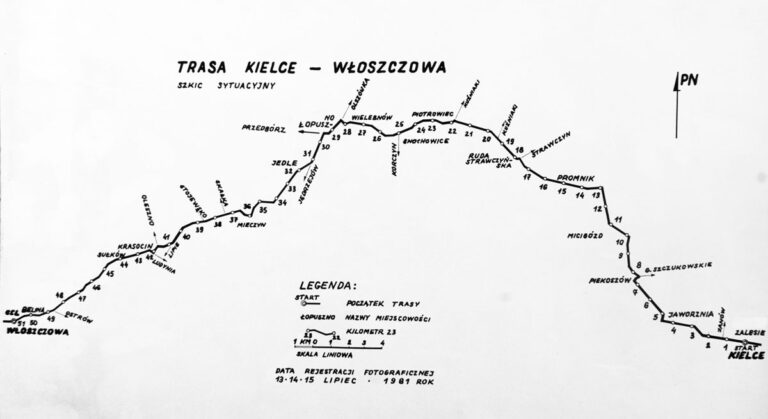

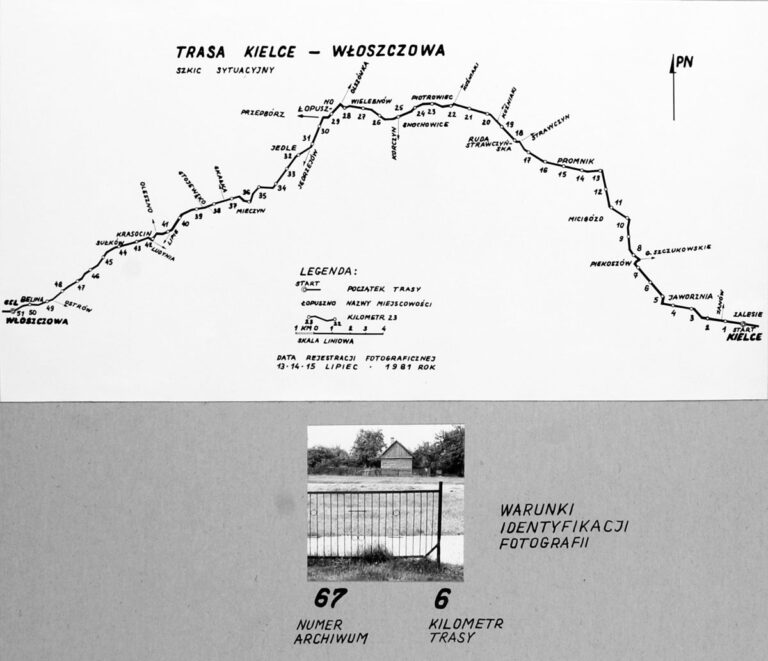

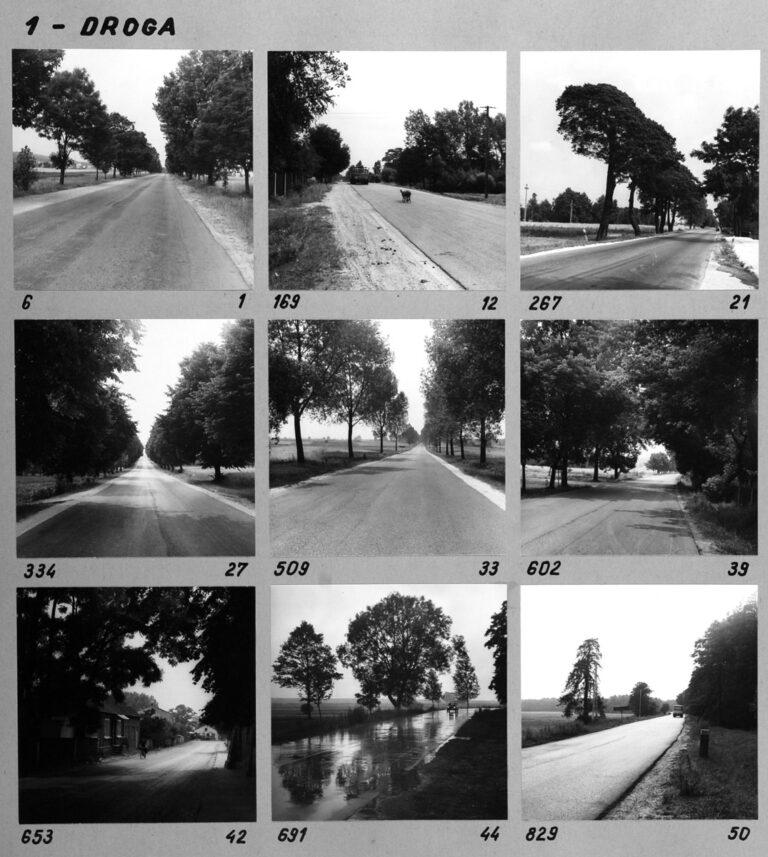

The work of Paweł Pierściński falls within a spectrum extending between the artistic style typical of the Kielce School of Landscape and straight documentary photography. The extremes of this spectrum may be represented, on the one hand, by the ‘Landscape Geometry’ series and, on the other, by the 1981 ‘Kielce-Włoszczowa’ project (for the purposes of this comparison, I deliberately pass over his experiments with photomontage or noble photographic techniques from the “Landscape Interpretations” series). ‘Kielce-Włoszczowa’ is the result of the photographer’s 3-day trip along the route between the towns of Kielce and Włoszczowa. He documented the elements he came across on the way to group them later into twenty-four thematic categories. The end result were panels with sets of photographs depicting the individual items, including ‘road signs’, ‘shrines’, ‘trees’, ‘road’, ‘side roads’, etc.

Most of Pierściński’s photographs display features of either of these two aesthetic canons. You can even try and put them on an axis – some closer to the straight photography end, others – the more aesthetic and carefully composed ones – closer to the other extreme.

Part 3 – “BE LIKE PAWEŁ PIERŚCIŃSKI”

Given the specificities of Paweł Pierściński’s photographs, there are at least two different keys to organising a heritage exploration trip inspired by his work:

A. THE ARTISTIC KEY – “TO BE LIKE PAWEŁ PIERŚCIŃSKI”:

Have a look with your students at a choice of Pierściński’s art photographs (e.g. from the ‘Landscape Geometry’, ‘Earth’, or ‘Landscape Moods’ series) and discuss their characteristic features together. Then go on a walking trip in your area and try to show it in the way the members of the Kielce School of Landscape would.

After the trip, view the photographs together and try to answer the following questions:

– What elements were you looking for in the landscape when you were composing the pictures?

– What elements did you avoid in your pictures?

– What did you pay attention to?

– Have you discovered anything new for yourself by looking at the space you know in a new way? Does such different way of looking – focused on form and composition – let you notice things that you do not notice on a daily basis?

B. THE DOCUMENTARY KEY – “FOLLOWING THE FOOTSTEPS OF PAWEŁ PIERŚCIŃSKI”:

Search the Paweł Pierściński Archive to find photographs of places where you can go together. To do this, you can use the various filters available on the website, e.g. search by city name or keywords. Once you manage to find such a place, look carefully at the photographs, and preferably take them with you on your trip (as printouts or in a smartphone or tablet). Once you arrive on the spot, try to find and re-take the frames once captured by Pierściński as accurately as possible.

After the trip, view the photographs together and try to answer the following questions:

– What elements from Pierściński’s photographs have survived to this day?

– What new features or things have appeared in the surroundings? Why has this happened and what does it mean?

– What has disappeared? Why has this happened and what does it mean?

A similar experiment was carried out in the summer of 2020 by the Kielce Art Exhibitions Bureau, who organised an open air workshop dedicated to Pierściński’s ‘Kielce-Włoszczowa’ project. Twenty photographers followed Pierściński’s footsteps looking for places where he had taken his photos 39 years earlier. Pierściński had made things easier for the participants, writing under each photo the road kilometre where he had taken the picture. The participants of the 2020 workshops produced similar panels to those created by Pierściński decades earlier and displayed them at their post-workshop exhibition ‘Kontaksty – Kielce Włoszczowa 2020’.

If you cannot go on a trip, compare the panels produced by Pierściński and those created during the 2020 BWA Kielce workshops and try to answer the above questions.

C. EXPLORE THE GOOGLE MAPS

If you cannot go on a trip to places photographed by Paweł Pierściński, you can look for them on Google Street View. Most of the pictures from the Archive are described by geographic coordinates. Just copy and paste them into the Google Maps search box (remember to separate the latitude and longitude coordinates with a comma). This will take you to the place photographed by Pierściński. In addition, many places on Google Street View have been re-photographed many times (the earliest pictures date back to 2009). So in addition to comparing how Paweł Pierściński rendered these places with the way they look today, you can also trace back the changes that have occurred over the last 10 years.

Naturally, we encourage you to go outdoors whenever possible.

***

Tomasz Kaczor, Szczepan Żurek (Towarzystwo Krajoznawcze 'Krajobraz')

In the section about the history of heritage tourism, we used the article:

Cyryl Skibiński, „Polskość na wczasach”. Magazyn Kontakt 24/2013 (https://magazynkontakt.pl/polskosc-na-wczasach)

Filters